4000 Islands: a gateway to Laos

by Frédéric Gousset

Summary of the History of Khone Island - Part 1

Until very recently, navigation on rivers and their tributaries was the main mode of transport in Southeast Asia. Indeed, until the construction of modern roads in the first half of the 20th century, the monsoon season made the tracks impassable for almost half the year.

For centuries, the Mekong was therefore the preferred trade route for the people living along its banks. However, the significant variations in its water regime (floods and ebbs), as well as its course dotted with rapids and even waterfalls, made navigation sometimes perilous if not impossible on certain sections of its course.

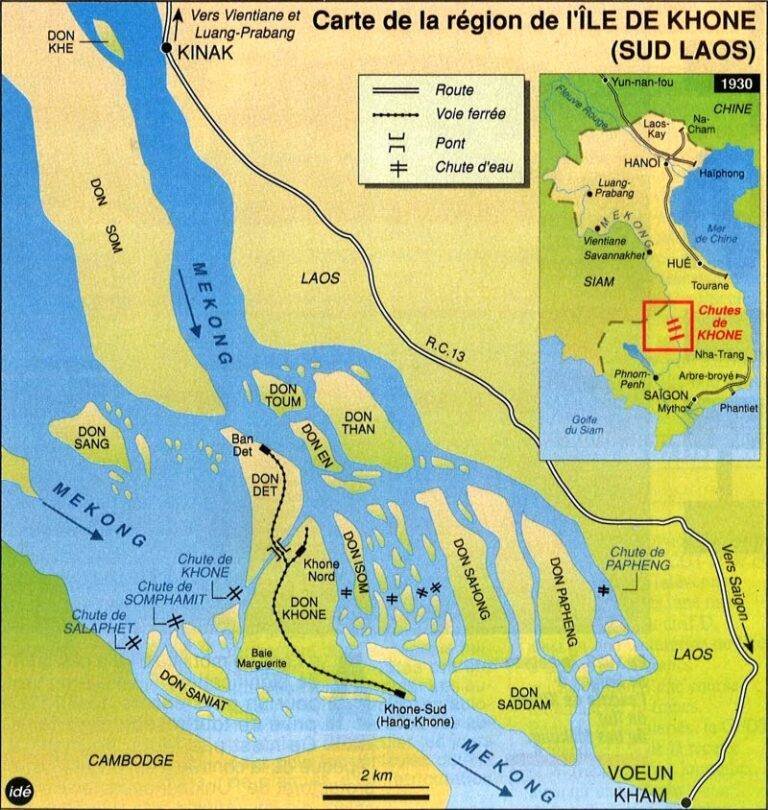

Because of their nature, the Khône Falls form a natural obstacle to navigation and because of its location and topography, Khône Island has always formed the link between the Lower and Middle Mekong basins. Sometimes located in the middle of a political entity, but more often acting as a natural border between two political entities, the control of Khone Island has always been of strategic importance to them.

At this point, the Mekong is about 11 km wide, interspersed with 6 main islands and numerous rocky islets. The river flows here either in powerful rapids strewn with rocks or over waterfalls that can be up to 14m high. The Khone Falls were and remain impassable for commercial traffic.

To cross this natural obstacle to navigation, the boatmen had to choose Khone Island because, by its geography, it was accessible from the north and the south, whatever the water level, for rafts and pirogues. In addition, the distance needed to tranship goods was shorter than on other islands.

Crews coming from the north, for example, would dock at the northern end of the island, unload their goods and disassemble the transport rafts. The goods and the materials constituting the rafts were transported on the backs of men and pulled by buffaloes either to the beach of Khong Nyay during the low water season, or a little south of the Khone Pa Soy falls during the high water season. The pirogues then crossed the perilous rapids of the Hou Sahong or Hou Sadam with ropes and poles, depending on the water level. The crossing of these rapids lasted from 7 to 10 days on the way up and 3 to 5 days on the way down and was very dangerous for the pirogues as well as for the boatmen. Accidental deaths during this operation were not uncommon and the pirogues rarely emerged unscathed. The pirogues were then repaired, reassembled into rafts and reloaded for the rest of the journey.

It can be assumed that Khone Island has been inhabited for many, many centuries, with the inhabitants living from fishing, rice cultivation, trade and hiring out their services as guides to cross the rapids or as labourers to tranship goods. However, the oldest remains found on the island date with certainty from the Angkorian period (9th century). Indeed, the temple of Wat Khone Tai gathers the remains of a Khmer temple whose foundations could be prior to the 9th century.

The first written records of Khone Island by Westerners were written by the Dutch sub-merchant Gerrit Van Wuysthoff and his assistants during their trip to Vientiane (1641-1642) and by the Piedmontese Jesuit missionary Giovanni-Maria Leria in 1642. The Dutch discovered a wooden sign, written in Khmer and Lao, marking the border between Laos and Cambodia. This sign was located halfway between ThaXayNam (Kong Nyay) and Khone North. In his account, Van Wuystoff names the island of Khone “Saxenham”, later translated by P. Lévy as “The Island of the Oath”, probably alluding to the agreement made between the Khmer and Lao kings concerning the location of the border between their kingdoms.

Map of Khone Falls

Traditional dug out raft, or pirogues

Plan of a Lao transport raft

Some Khmer remains at Wat Khone Tai

Already at that time, and certainly for several centuries, Don Khone was the gateway to Laos. Even today, as a vestige of this glorious past, the inhabitants of the region refer to the area of the Mekong north of the islands of Khone, Ixom, Sahong and Sadam as “ປະຕູ ເມື ອງລາວ” (the gateway to the Lao kingdom).

Around 1694, following problems of succession to the throne after the death of the last king of Lan Xang, Surinyavongsa (1633-1690), Pha Khu Phon Samek, the most popular and revered monk in Laos, left Vientiane with more than 3000 followers. Their wanderings took them to Phnom Penh, where the Cambodian ruler ordered them to leave his kingdom. On their way, and under the leadership of Pha Khu Phon Samek (also known as Phra Kru Nyot Keo and Pha Khu Khi Om), they founded Buddhist pagodas in Stung Treng, Don Khone and Don Khong between 1700 and 1708. At each of these stages, the faithful settled on the spot to take care of these pagodas. From their passage to Don Khone we still have the That (stupa) leaning against the temple of Wat Khone Tai, and the Chao Muang of Khong were, until recently, descendants of the devotee that Phra Khu Phon Samek had designated as responsible for the pagoda of Khong.

Pha Khu Phon Samek and the rest of his followers continued until Don Deng then the old leader of the Muang of Champasak entrusted him with power. He reigned for about 5 years before bringing in Chao Nokasat, one of the grandsons of the last King of Lane Xang and crowning him King of Champasak in 1713.

That Phra Khu Phon Samek

In the second half of the 18th century, the kingdom of Champasak extended its borders well beyond the Khone Falls, encompassing part of the present provinces of Stung Treng and Preha Vihear (Cambodia).

It was in 1778 and 1779 that things changed. The Siamese led an attack on the kingdoms of Champasak and Vientiane. These victories put an end to the independence of these two Laotian kingdoms, only the Kingdom of Luang Prabang retained a semblance of independence. The King of Champasak retained his throne, but owed allegiance to the King of Siam and was flanked by Siamese administrators who managed the vassal kingdom. Don Khone thus became Siamese as well as the entire surrounding region.

This is the state of affairs that the members of the Mekong Exploration Commission, led by Doudart de Lagrée, discovered during their expedition which began in 1866. Following the colonisation of present-day Vietnam and the creation of the Cambodian Protectorate, the appetite of the French colonists was not satisfied. They energetically sought to find river access routes that would link their colonies to the heart of China. An exploration commission was then created and left Phnom Penh on May 1, 1866 to travel up the Mekong by dugout canoe to China for two years. These explorers stayed for a week on Khone Island in order to carry out the first mapping and to explore the possibilities of crossing the rapids.

In 1869 and 1879, the exploration mission of RHEINART and MOURIN D’ARFEUILLE aims to study the rapids from Préapatang (between Stung Treng and Kratie, in Cambodia) to the Khone Falls, in order to evaluate the possibility of sending steamships there. From this date onwards, the French organised numerous explorations in Laos in order to discover the natural resources, the political and military organization and above all the possible routes for trade.

Etienne Aymonier, during his first visit to Khone in October 1883, described the island of Khone as follows: “The village of Khon is quite pretty, with numerous fruit trees surrounding about forty huts, sparsely scattered along the edge of a small arm ten metres wide, which has the appearance of a large millstream. At the top of the village is a modern pagoda, at the bottom another older but abandoned pagoda houses a large, well carved pedestal linga, a remnant of the old Brahmin cult in the days of Cambodian power. Behind the village lies a plain of rice fields which occupy part of the island. The village and the island are under the authority of two mandarins, Luong Banha Vichit and Khun Si Raksa Phon. The inhabitants are Laotian and mainly grow glutinous rice. Some of the rice from Khon is bartered for Cochinchina salt from Stung Treng.

At that time, many goods passed through Khon from Laos, including cotton, benzoin, cinnamon, shellac, gum gutte, silk, cardamom, ivory, horns, skins, tobacco, rice and teak.

It was in 1887 that the first small French steamers, the “Mouette” and the “Doc-Phu-Ca”, commanded by Lieutenant de Vaisseau de Fésigny, arrived at Khone Island and that the members of the expedition mentioned the possibility of installing a railway for the transhipment of goods from one reach to the other. This event was considered a feat by the French press, a feat repeated the following year by the liner “Cantonnais”, commanded by Lieutenant Heurtel and piloted by Guissez.

In 1890, the Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales de Cochinchine, a private company subsidized by the French government with a monopoly on river transport on the Mekong, provided a link between Phnom Penh and Khone- Sud. That year and the two that followed, the French Navy tried, without success, to get a small steamboat, the “Argus,” to cross the Hou Sahong rapids.

The Siamese still controlled the Laotian territories, and they took a very dim view of the growing interest of the French. In 1888 they had founded a military camp in Champasak to train Laotian recruits and reinforced their presence in the region. In 1892, the posts of Muang Sène, Muang Khong (both on Khong Island) and Khone were fortified by the Siamese, as well as the islands of Don Som, Don Sadam, Don Deng, and the village of HatKhikhoai (Nakasang).

It was in 1893 that the story accelerated: in March, Auguste Pavie, former French Consul of the Kingdom of Luang Prabang, informed the Thai government that France intended to secure the territories on the eastern bank of the Mekong Valley. The Siamese protested but the French continued with their plans. The French annexation of the Lao-Cambodian border region began in April 1893. Under the authorization of Chancellor Bastard, the French Resident Superior of Cambodia, a military column was sent to Stung Treng on April 1. The French force known as the “Mission Bastard” was commanded by Captain Thoreux and comprised 180 mostly Vietnamese soldiers. After securing Stung Treng, Thoreux’s troops moved north to Don Khone on 4 April. Despite protests from the Siamese government against his actions and the defence of the territories by the Siamese military outposts, the French gained control of the main border posts of Cambodia and Laos.

The conquering troops were relieved in April by Lieutenant Pourchaud accompanied by 50 Vietnamese riflemen. At the beginning of May, the Siamese troops besieged the garrison of Khone and set up a blockade which lasted nearly two weeks before French troops came to free the besieged.

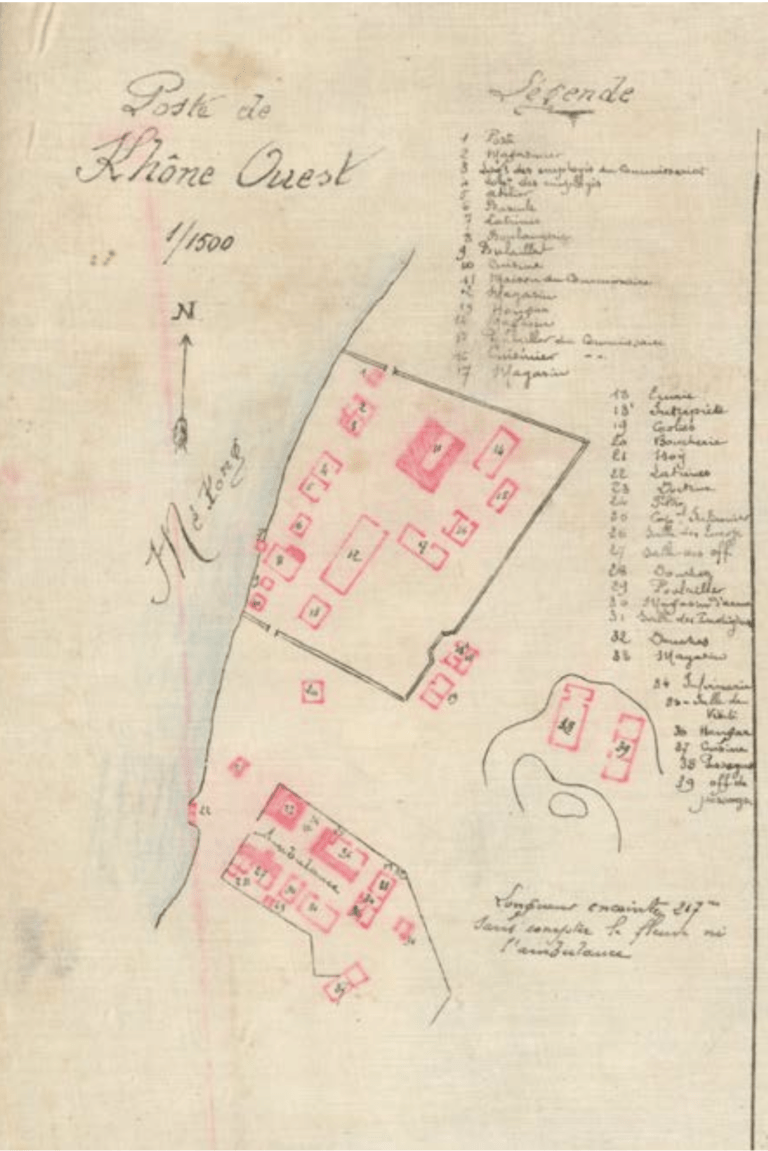

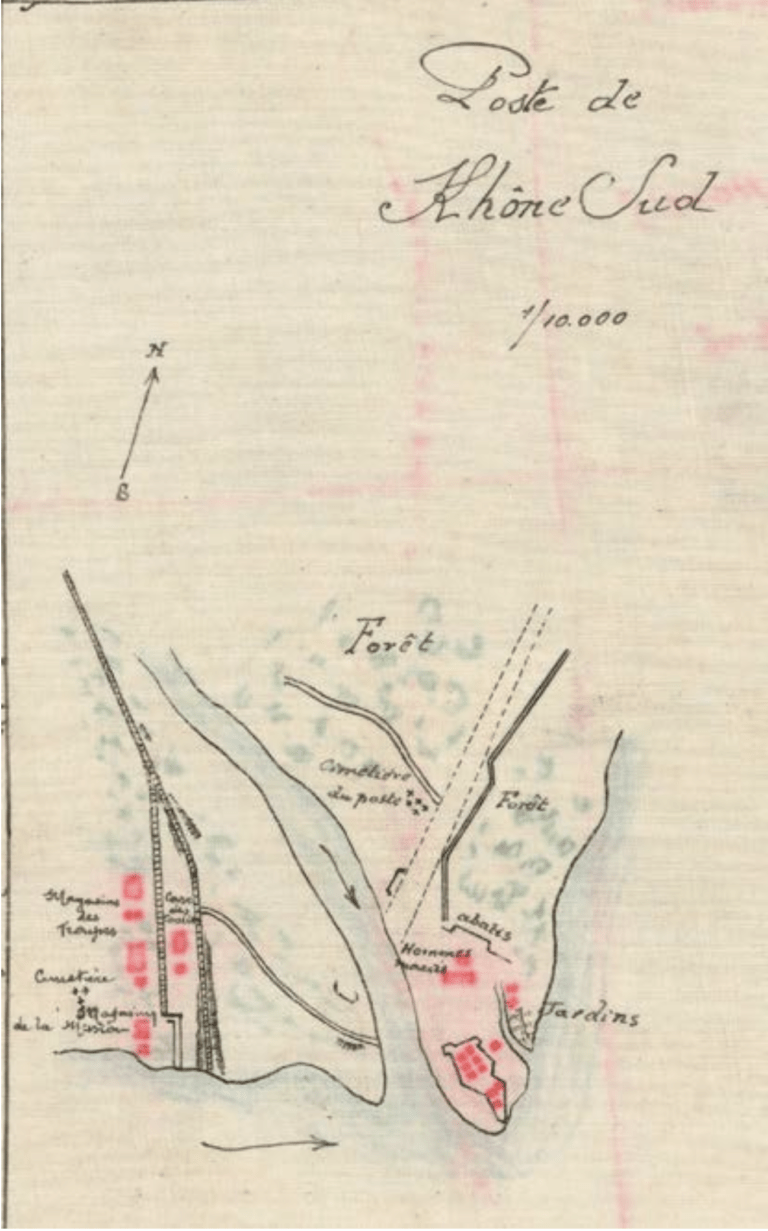

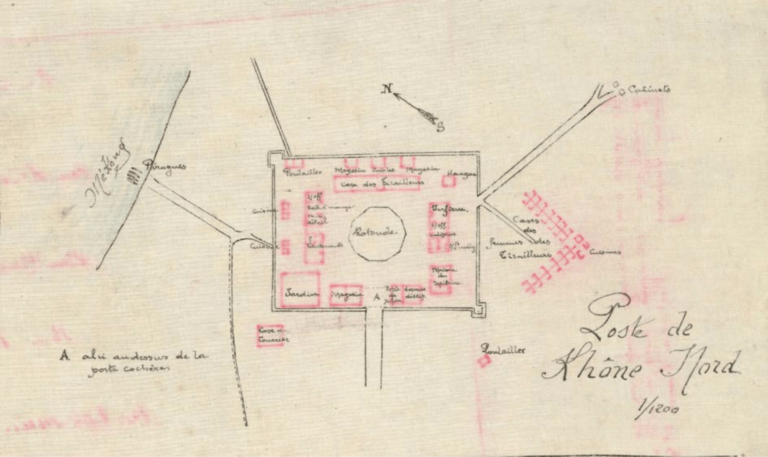

The French quickly built three forts (Khone-South, Khone-North, Khone-West), and undertook the construction of a 3km long Decauville railway linking Khong Nyay beach to Khone West. The aim was to tranship river gunboats as quickly as possible to the north of Khone Island in order to ensure French military superiority and to take control of the Laotian territories on the eastern bank of the Mekong.

French forts of Khone island in 1893

This is the end of Part 1 of Southern Laos History.

continue with Part 2 – The History of Laos: 1850 to Present